Guest post by: A.T. Grant, Ph.D., Applied NeuroKnowledge

Marketing research and advertising studies currently use Facial Action Coding (FAC) to test dynamic material looking at both overall emotional response and moment-by-moment changes. At Affectiva, the leading purveyor of FAC data, studies have not, yet, been conducted with static marketing materials such as logos, print/web ads, and package designs.The Wild Animal Study is basic research using FAC to study emotional response to static images. The overall goals of the study are to use a set of photos to elicit emotions, analyze the responses, and establish analytic tools to enable economical testing of large numbers of images. The design can then be adapted and the method used with a variety of marketing materials.

Eliciting Emotions

Why study Wild Animal photos? We are marketing researchers, after all. For this basic research, however, we need to simplify the neural-processing demands, isolating emotional response without cognitive overlay to the extent possible. The world of Wild Animals meets our requirements for photos generating intrinsic emotional responses.

-

Inherently engaging: Wild Animals run the gambit from endearing to terrifying

-

Flexible emotional content: type of shot, interaction between pairs

-

Familiar: known without identification, words, or graphics

-

Impersonal: no farm animals or pets

-

Unfettered: no marketing or purchase history

The choice of uncomplicated Wild Animal photos provides transparency of our own responses. This emotional self-awareness gives us a unique opportunity to compare our own sense of positive and negative Valence to that measured by Affdex FAC.

Method

The stimulus array includes 35 purchased stock photos of Wild Animals in a wide variety of natural settings. Carefully selected photos populate a factorial design with seven categories of animals: bears, big cats, birds, reptiles, pachyderms, primates, and a miscellaneous group. Within each category, five types of content are included, as shown below.

Portrait: headshot

Full Body: body shot

Family, mother and offspring facing the camera

Bonding: mother and offspring in nurturing interaction

Romance: consenting pairs in tender moment

A final sample of 475 online participants viewed each photo for 3 seconds. Webcams recorded facial responses. Affdex FAC analysis generated moment-by-moment emotion metrics (14/sec). Subsequent baseline calibration at the participant level for each photo eliminated order effects.

Selected Valence rank-order results presented here demonstrate our success at eliciting and measuring emotional response to static images. Additional details, findings, and discussion will follow this first release of results from The Wild Animal Study, including analysis of the factorial design, moment-by-moment changes, as well as gender and age group differences.

Come Feel with Me: Valence and Emotional Self-Awareness

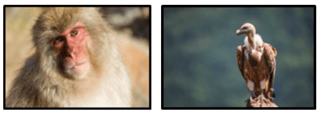

Faces engage the brain more than any other visual information. Expressions are the key to nonverbal communication. Friend or foe, their face unlocks a wealth of information in the brain of the beholder. Research on the evolution of facial expression shows primates use expressions similar to ours. 1, 2

This Rhesus Monkey Portrait has the highest Valence in the study (Rank 1). It closely resembles a human face with a captivating look in its eyes.

This Rhesus Monkey Portrait has the highest Valence in the study (Rank 1). It closely resembles a human face with a captivating look in its eyes.

In stark contrast is the Full Body Vulture, achieving the most negative Valence (Rank 35). Compared to the engaging Rhesus Monkey, it is not a surprise that emotional response to the unappealing Vulture is far less favorable.

One of the strengths of The Wild Animal Study is that we can informally use our emotional self-awareness to validate the findings. We know it is difficult to identify and verbalize the complexity of emotional response, but it is easy enough to know we respond more favorably to that Rhesus Monkey than this Vulture.

We expect faces to be the most evocative of emotional response, but animal faces generate only half the activity of human faces in areas of the brain critical to processing facial information. However, animal faces show 2.5 times the activity of response to full-body animals. Consistent with these MEG (magnetoenephalography) results, we find a striking difference between Portrait and Full Body Wild Animal photos. 3

Joining the Vulture in the bottom ranks are three Full Body Wild Animal photos: Indian Rhino (Rank 32), Alligator (Rank 33) and Antelope (Rank 34).

What do you feel when you look at these photos? Do they elicit negative emotional responses? Would a more ‘friendly’ Full Body photo generate a positive response? Of course, but not so much.

The highest Valence among the Full Body Wild Animal photos is the Giant Panda (Rank 16). This middle-of–the-pack ranking is a surprise in that the Giant Panda is so adorable. It is highly publicized and much in demand as stuffed animals and other product designs. The World Wildlife Fund uses a Giant Panda image in their logo. Such factors create a favorable cognitive component, that would appear later.

The highest Valence among the Full Body Wild Animal photos is the Giant Panda (Rank 16). This middle-of–the-pack ranking is a surprise in that the Giant Panda is so adorable. It is highly publicized and much in demand as stuffed animals and other product designs. The World Wildlife Fund uses a Giant Panda image in their logo. Such factors create a favorable cognitive component, that would appear later.

Our findings show more positive response to headshots than body shots; Portrait photos (mean Rank 17.4) elicit higher Valence than Full Body photos (mean Rank 29.1). Nevertheless, while the top ranked photo is the human-like Rhesus Monkey, the other Portraits are much further down the rank order.

The next Portrait (Rank 13) is the Endormi Lizard. It cannot pass as a close relative to humans. It does have, however, a certain facial charm that could become an eye-catching animated character.

The next Portrait (Rank 13) is the Endormi Lizard. It cannot pass as a close relative to humans. It does have, however, a certain facial charm that could become an eye-catching animated character.

What happens between the Rhesus Monkey and the Endormi Lizard? What generates higher Valence than Portrait and Full Body photos? Relationships. Especially those showing strong emotional connection.

Feel the love. Love the feeling. ©

Does the emotional response become more positive when we show two Wild Animals? We tested three types of relationships in two-animal images.

- Family: An adult, presumed the mother, with a young child. There is no interaction between the two. They pose next to each other and face the camera much like the headshots in Portrait photos.

- Bonding: Again, an adult, presumed mother, with a young child. Here, however, they are in interaction, and neither are facing the camera.

- Romance: A Wild Animal adult couple. They are also in interaction with a physical gesture of affection.

Family

The mother and child image is a classic example of a strong emotional connection and the joys of new life. Four Wild Animal Family photos have high Valence rank order, White Rhino (Rank 8), Brown Bear (Rank 9), Camel (Rank 10), and Lion (Rank 11). The overall average rank of 14.9 is lower than the 17.4 obtained by Portraits indicating that the presence of a child heightens emotional response to Wild Animal photos.

Bonding

Formation of a secure attachment between offspring and parent or caregiver, termed ‘bonding,’ impacts abilities to interact, communicate, and form relationships throughout life. Attachment bonding is essential for non-human animals as well as humans.

There are four distinguishing characteristics of attachment bonding: 4

- Proximity Maintenance: Desire to be near

- Safe Haven: Seeking comfort and safety

- Secure Base: Exploring the surrounding environment

- Separation Distress: Anxiety when absent.

The Wild Animal Study shows the power of bonding images to generate strong, positive emotional response in our participants. The mean rank for Wild Animal Bonding photos is 11.1 compared to 14.9 for Family photos. Four of the Bonding photos are in the top ten.

White Tiger Bonding (Rank 4)

White Tiger Bonding (Rank 4)

The tiger cubs usually stay with their mother until they are between 2 and 3 years old and strong enough to venture out into the jungle to live on their own.

Hippopotamus Bonding (Rank 5)

Hippopotamus Bonding (Rank 5)

After birth, the hippopotamus mother and calf remain isolated from the herd for about two weeks. She nurses and bonds with her calf foregoing grazing until the calf can safely accompany her back to the herd where she continues to nurse for at least 8 months.

Koala Bonding (Rank 6)

Koala Bonding (Rank 6)

A newborn joey is blind and earless. The tiny creature makes to its mother's pouch where it stays, safely tucked away, growing and developing. At about seven months, the joey leaves the pouch to eat leaves, but returns to nurse. By one year old, it stops nursing, and moves out of the family home.

Duck Bonding (Rank 7)

Duck Bonding (Rank 7)

There is a unique form of bonding, limited to birds, that is one of the strongest forces in nature: imprinting. Upon hatching, ducklings develop a strong attachment bond to the first moving object they encounter, usually the mother duck. They follow their mother for the next 50 to 60 days while maturing and developing their ability to fly.

When you look at the Wild Animal Bonding photos, do you enjoy the special relationships captured in them? We know you do, just like our participants. Your face shows it!

Romance

Wild Animal Romance photos include two of the highest ranked photos. However, the remainder fall short (mean Rank = 16.4). The wide range of rank (2 to 30) suggests that some romantic gestures communicate better between wild animals than to us.

The Wild Animal Romance photos show small actions that convey affection, bringing a pair closer. Iguana Romance and Chimpanzee Romance are Valence Rank 2 and Rank 3, respectively.

The Wild Animal Romance photos show small actions that convey affection, bringing a pair closer. Iguana Romance and Chimpanzee Romance are Valence Rank 2 and Rank 3, respectively.

The romantic aspect of these Wild Animal photos may have alluded our participants: Penguin Romance (Rank 22), and Indian Elephant Romance (Rank 25).

When we view such relationship photos, Family, Bonding, and Romance, we feel the love reflected in warm pictures of two Wild Animals. Our emotional self-awareness knows we love the feeling, and it shows in facial expressions.

Emotional Contagion

The term ‘emotional contagion’ characterizes the impact of emotional display on the viewer. Hatfield, et al. 5 consider the role of mimicry, the copying of physical characteristics, to be central to this process.

- Step 1: A person has a sensory experience of another’s physical expression of emotion.

- Step 2: They mimic the facial expression, body posture, or vocal characteristics.

- Step 3: Feedback from the facial, or other, muscles of mimicry leads to the adoption of the emotion embedded in the original expression. Thus, perception drives mimicry drives emotions.

In the Wild Animal Study, however, there is no mimicry. The facial expression can only reflect, not cause, the emotion. Perception drives emotions. Thus, we show the impact of a visual display of emotion makes a ‘feedback’ step unnecessary for emotional contagion.

- Step 1: A person views an image of an emotional relationship.

- Step 2: In response, the person feels the emotion.

- Step 3: The emotional experience creates a facial micro-expression.

Further investigation of our emotional contagion findings includes examination of the moment-by-moment course of emotional response to relational content (Family, Bonding, and Romance) as well as comparison to the weaker responses to Portrait and Full Body photos.

Conclusions

The Wild Animal Study demonstrates the ability to elicit emotional response from static images. The analytic process provides cost efficiencies that enable testing large number of images. The results of the FAC analysis presented here show meaningful differences attributable to photo content:

- Portraits generate a more favorable response than Full Body shots which is consistent with EMRI findings.

- Photos of relationships between Wild Animal pairs generate more positive Valence than photos of a single one.

- Attachment bonding is the strongest relationship, perhaps reflecting its unique importance in human development.

The findings reported here are supported by emotional self-awareness; we intuitively see the validity of the results.

Further analyses, to be presented in future publications, cover gender and age group differences in range, and the moment-by-moment dynamics of emotional response.

Interested in knowing more? Considering whether and how to integrate static image FAC into your marketing research? Contact A.T. Grant at 214-454-0404 or email at@atgrant.com. Website: NeuroKnowledge.org

About The Wild Animal Study

Three companies collaborated on The Wild Animal Study. Applied NeuroKnowledge provided research methods, experimental design, and analysis. Decision Analyst fielded the study using their American Consumer Opinion® online panel, contributed to research design and analytics. Affectiva processed webcam videos of facial response. This report is copyright of Applied NeuroKnowledge Corporation, 20172/3/2017.

About The Author

A.T. Grant, Ph.D. is a research methods specialist. Her background is a unique combination of experimental psychology, cognitive neuroscience, and marketing research. Her company, Applied NeuroKnowledge Corporation, specializes in the development and implementation of consumer neuroscience research techniques. A.T. offers consulting and project management services.

214-454-0404

Marketing Research

Applied NeuroKnowledge, Dallas, TX

Nielsen Consumer Neuroscience, Shanghai, CN

(Formerly Nielsen NeuroFocus)

MARC Research, Irving, TX

Eric Marder Associates, New York, NY

Academic Research

Center for Brain and Cognition, University of California, San Diego

(Formerly Center for Human Information Processing)

Cognitive Psychophysiology Lab, University of Illinois, Urbana

Brain Research Institute, University of California, Los Angeles

Ph.D. University of California, Santa Barbara

References:

[1] L. Parr & B. Waller, Understanding chimpanzee facial expression: Insights into the evolution of communication. SCAN (2006) I, 221-228.

[2] J.P. Gulledge, S. Fernández-Carriba., D.M. Rumbaugh, et al. Judgments of Monkey’s (Macaca mulatta) Facial Expressions by Humans: Does Housing Condition “Affect” Countenance? The Psychological Record, (2015), Volume 65, Issue 1, pp 203–207

[3] E. Halgren, T. Jaij, K. Marinkovic. V. Jousmaki, & R. Hari, Cognitive Response Portrait of the Human Fusiform Face Area as Determined by MEG, Cerebral Cortex, (2002), Volume 10, Issue 1, pages 69-81

[4] J. Bowlby, A Secure Base. (1988), New York: Basic Books.

[5] E. Hatfield, L. Bensman, P. Thornton, & R. Rapso, New Perspectives on Emotional Contagion: A Review of Classic and Recent Research on Facial Mimicry and Contagion, Interpersona, (2014) Volume 8, Issue 2, pages 159 - 179.