What does your smile mean to you? It’s a question that elicits an emotional response: often, people can’t really describe in words what it would mean to have their smile taken away. We use our smile every day when communicating with others, and we don’t do it consciously. It’s our way to interact with other humans and makes us who we are.

In our latest Affectiva Asks podcast, we interview facial reconstructive surgeon Dr. Joe Dusseldorp. During the interview, he talks to us about his mission to rebuild smiles, his patients that inspired this work, and how he is using Affectiva’s technology to build a program to measure the success of how his patients experience facial expressions of emotion after surgery. His research was also just published in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Journal.

Let's start with a quick introduction of yourself and what you're currently working on.

I'm a plastic surgeon, and I'm really interested in conditions that involve the facial nerve—that means that one side of the face doesn't work very well. I also work with those diagnosed with Bell's palsy, which is a condition where one side of the face doesn't work well sometimes due to a viral infection. We worked together with doctors in the United States, where I've been in residence at the Mass. Eye and Ear Hospital, and we put together a program to use AI to help these patients.

You had a really interesting path to Affectiva’s technology, which I believe started when you saw a talk at our first Emotion AI Summit: can you share that story with us?

I was living in Cambridge and I found out that there was this Emotion AI Summit at MIT and the work that Rana and team Affectiva were doing. I was pretty amazed at the synergy between trying to understand what people's faces are telling others emotionally and what happens with facial palsy, and so I decided to go to this Summit.

I was listening to a talk by Kantar Millward Brown’s, Graham Page, who's a long-term collaborator of Affectiva. He was talking about using AI to decrypt emotion in video clips of people watching advertisements. And I thought, "that's exactly what we do when we're trying to understand how our patients feel emotion." We ask them to watch a funny video, we film them and we make an assessment of their ability to smile when they're laughing. It's something that we do very crudely, compared with the tech at Affectiva. So collaborating was something that I was pretty excited about: since then, we had a great collaboration that's led to quite an interesting publication all these years later.

What is the program you have developed?

We started to develop this concept of an emotionality quotient or the EmQ. What that is and why we're trying to turn it into an app doesn't currently exist at the moment: not that the technology isn’t capable, but an app presents some privacy challenges similar to a medical device. Right now, EmQ is interesting to us because not only do we see a benefit in people's ability to smile when we try and restore that, but our goal is to restore that smile to normal.

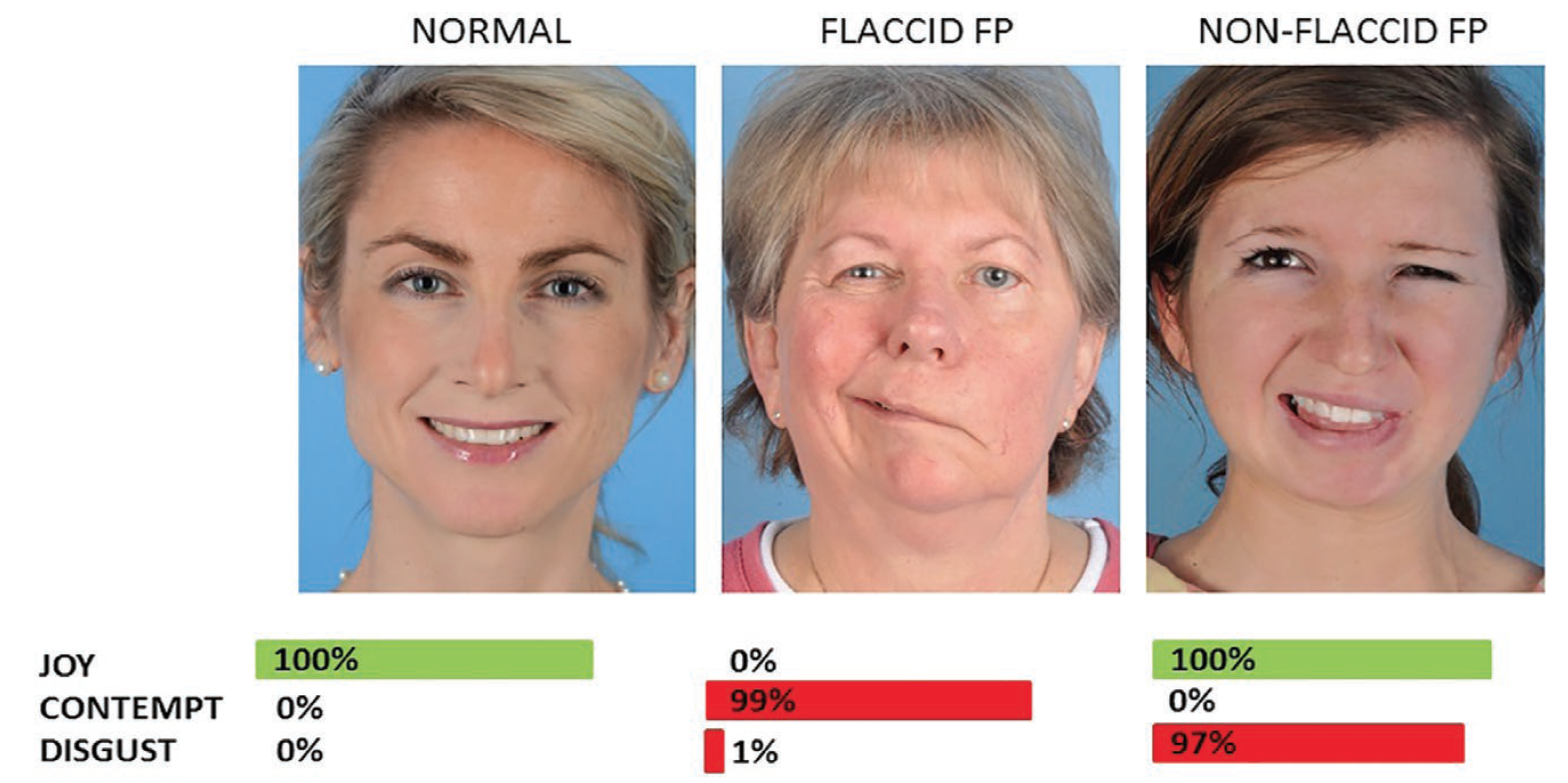

We measure our ability to do that with a before and after comparison using Emotion AI tech, then we measure the ability of our surgery to reduce a negative emotional affect. So looking like you are expressing disgust when you're actually trying to express joy is quite difficult for someone who has that problem. This means every time you smile, you look like you don't believe what someone is saying. So we wanted to calculate both: the positive benefit in terms of improving your ability to smile, but also taking away some of that negative emotion, something we didn't really expect to find until we used the technology and realized that it was there.

Can you talk a little bit more about how it works?

What we are doing is measuring every frame within a video clip of someone watching a funny video. We're trying to understand what's happening to the observer using AI tech, how much joy they express every time that person smiles. And we found it was pretty dramatic, when people had facial palsy they would express no joy when they tried to smile.

In fact, they expressed a pretty high amount of contempt, on average around 80% probability that someone would expect that they would imagine that the person was feeling contempt. So, that's quite an important bit of information for us to know and for patients to be aware of, because no matter how hard they try and smile, they weren't able to do it. Then we compared after surgery, and we found there was a total reversal of that in the data. The majority of cases that could be up around 80-90%, and we were able to reduce that negative emotion down to trace levels. That was the first time that we've been able to objectively quantify improvements in people's emotionality.

I know you're a plastic surgeon. Was there any specific patient or incident that inspired you to build this?

There are a couple of patients that stick out in my memory. One of them is a lovely woman who was a teacher for primary school children. Her smile was her currency and helped her connect with the children: and when she lost that, every time she smiled one side of her face would grimace and the other side wouldn't move. The kids then just kept asking what was wrong with her face. She had to stop her job and change her profession to just marking papers, losing all of the joy that she had from what she did. Patients like her drive me to want to get better outcomes in helping to give their smiles back.

Can you talk a little bit more about the Affectiva integration?

Really what it's doing is facial landmarking. So what that means is, it puts lots of dots all around the face and those dots, if you have a big enough data set, are really accurate. Once you can do that, you can apply it to any face and even faces that the application will have never seen before, like a facial palsy face, where one side of the face is really drooped. Once those points are all able to be placed accurately, the next step is to put those dots together into expressions, and those expressions over time are then mapped to emotion probabilities.

So the app is not saying this person is feeling happy or this person is feeling sad, they're just saying with these facial expressions all grouped together over time, the likelihood that this person is happy or sad is this percentage.

That was useful for us because first of all, the app could identify the face. In most machine learning apps which don't have a very big data set, they wouldn't have known where to put the dots, but Affectiva has such a massive data bank to pull from that we were able to really easily find all of our patients' faces. Then, we could knot emotion categories to facial expressions that the computer algorithm had never seen before.

What's the next step for this project?

The goal is to make it a free app that our patients download that has a direct link to their clinician. The power of this is that on their own phone, once the video has been watched, that'll create an output which is really a sequence of emotion scores which get sent to us. It bypasses the need for private information or video clips to be sent over the internet, can be done quickly and without a lot of computing power.

Do you have any other advice for those who are looking to build something similar?

Jump in. You don't really know where these things will take you, but what you can be sure of is there's power in data. I think that we underestimate that as clinicians, because we're used to making judgment calls on things, and I think we have to be a little more open to data and understand what it can give us.

We were able to analyze over 100 patients in about 15 minutes without having to manually do so, and that's extremely powerful and time-efficient -- which all of us are looking for. We are all looking for a way to do things without spending huge amounts of time in a research capacity, and these tools should become part of our day-to-day clinical practice to help us make better decisions.

.jpg?width=600&height=282&name=shutterstock_736552108%20(1).jpg)