Blog post by: Juliana Viola, Intern at Affectiva

Today in the US and around the world, women are undeniably underrepresented in politics. American women make up just 19.4% of Congress and 24.9% of state legislators. Globally, just ten women serve as head of state and nine as head of government. This lack of diversity brings huge consequences; time and time again, studies have documented how diversity can spur workplace innovation and boost productivity. Therefore, increasing the representation of women, specifically women of color, in government offices would likely lead to a more effective government.Along the same vein, as an avid news junkie, I have often noticed homogeneity in the panel discussions I watch on TV. Political panels in particular are often comprised of mostly men. I wondered how I could capture metrics about how panel members emote and participate in the discussion, and how these metrics might vary by gender. For example, how is airtime split between men and women? Since the American public relies on political talk shows for perspective, these panels would ideally represent a diversity of voices to interpret objective information.

I also wondered about the emotional climate of these debates. Which emotions are most prevalent in news debates, and what might this data suggest about the state of American politics?

As a senior in high school, I had the opportunity to answer these questions as an intern at Affectiva.

Data Collection

In order to answer the above questions, I downloaded a few thousand publicly available videos of news panel debates, using search terms like "Fox News panel discussion," "George Stephanopoulos Powerhouse Roundtable," and "Meet the Press panel" to generate the results.

In order to obtain emotion metrics about each video, I uploaded all of the videos to Affectiva's Emotion as a Service platform. These emotion metrics are estimated by automatically analyzing the facial expressions of the panelists in the video.

Next, in order to analyze how verbally assertive men versus women are, I examined how quickly male versus female panelists grabbed the floor following a pause in the conversation. To do this, I removed the audio from the video files, and processed the audio using Affectiva's speech-based gender estimation model, which is able to predict the gender of the person speaking in an audio file. I performed this analysis on a subset of my entire data set: a collection of CNN debates and a collection of Fox News debates.

Results

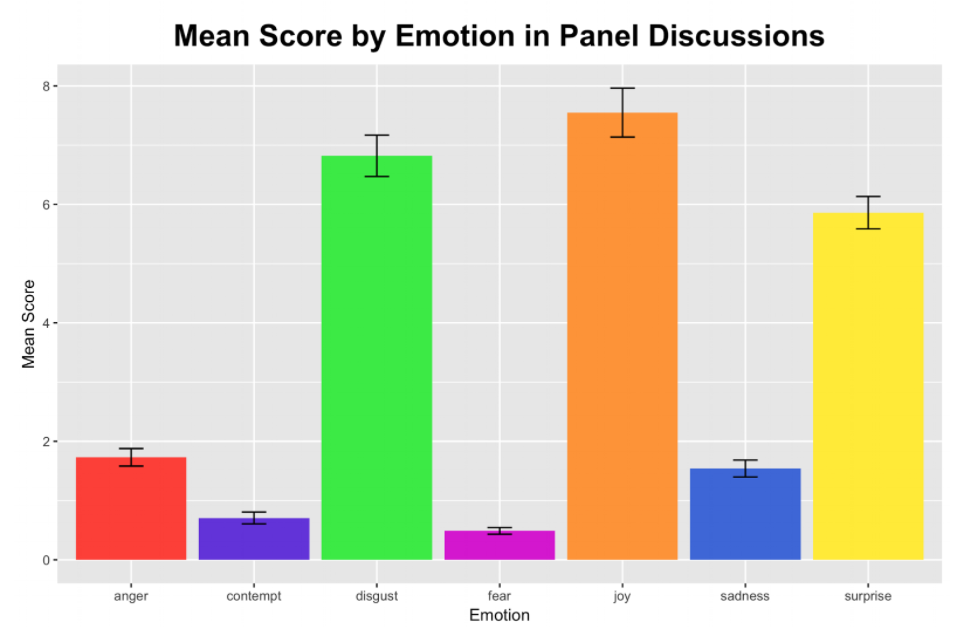

The mean scores for each emotion across all videos indicates that joy, disgust, and surprise were the most prominent emotions seen on panelists’ faces.

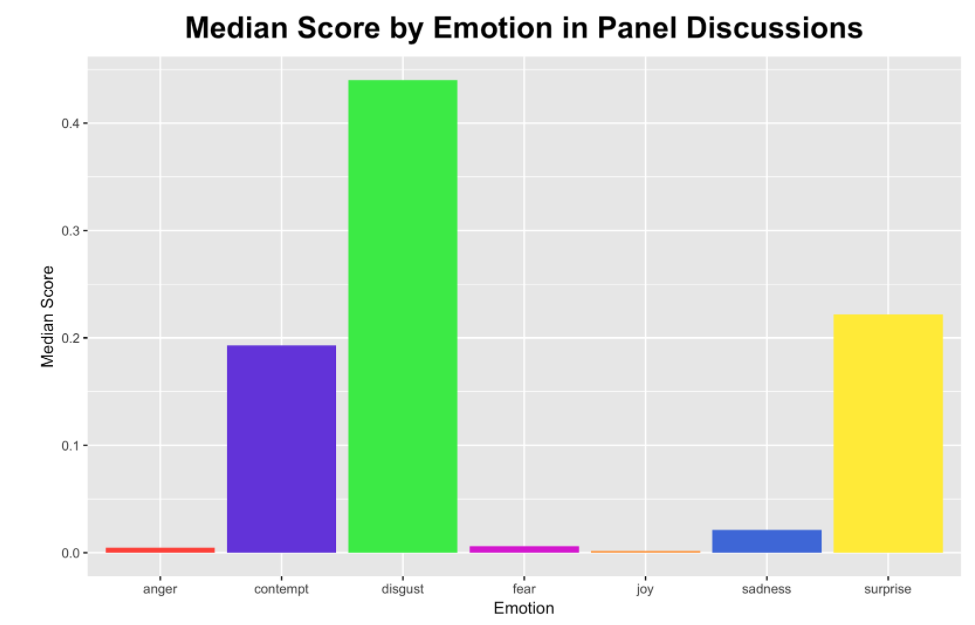

However, the median scores tell a different story: disgust, surprise, and contempt are most dominant.

So why does joy have the highest mean score of all the emotions but the lowest median score? This discrepancy stems from the distribution of joy in the panels -- for the most part, joy is sparse in panel discussions. However, when there are moments of joy, they are extreme, thus pulling up the mean score. Disgust and surprise are more consistent, each having both high median and mean scores.

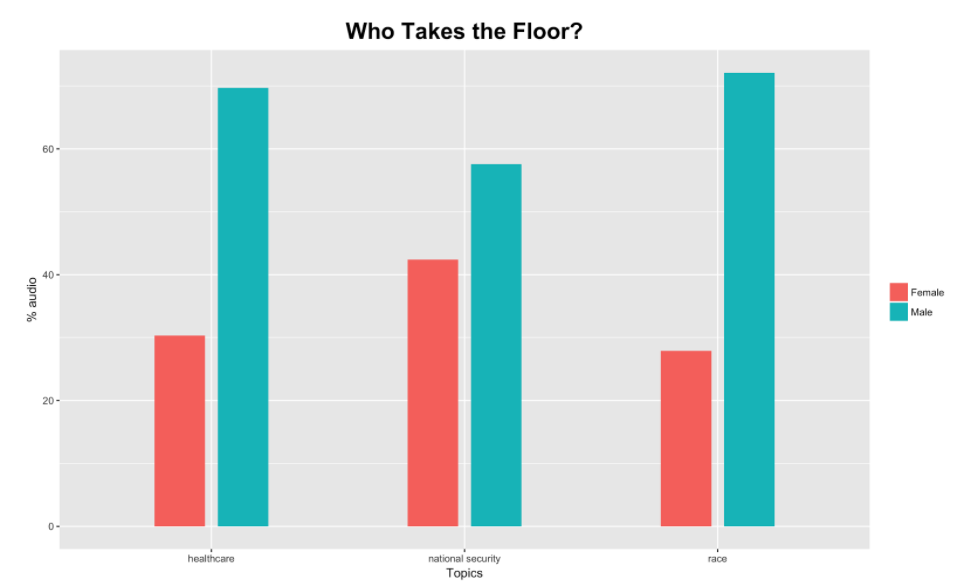

Our audio-based gender study revealed that following a pause in the conversation, women spoke first 38% of the time, while men spoke first 62% of the time. The results varied by topic, though -- when I grouped the data by keywords in the video titles, I noticed differences in the proportion of occasions when women jumped in first: 30% in healthcare-related debates, 42% in immigration/national security debates, and 29% in debates about race and civil rights.

Interpretations

What can the above results tell us about the American political climate? Let's first take a look at disgust. According to Paul Ekman in his book Emotions Revealed:

"[One] function of disgust is to remove us from what is revolting. Obviously it's useful not to eat something putrid, and social disgust in a parallel way moves us away from what we consider objectionable. It is... a moral judgement, in which we can make no compromise with the disgusting person or the disgusting actions."If disgust is common in American news debates, then perhaps compromise is lacking from these conversations. Over the past few decades, both political polarization and partisan antipathy have increased in the US -- and this growing, more intense divide is not conducive to compromise. Perhaps this divide also explains the high level of disgust in the data set; in future research, I would be interested monitoring the level of disgust in news debates over time from the 1990s to present day to see if disgust has surged alongside polarization and antipathy.

Despite some negative tones in these debates, there were some moments of extreme joy -- in other words, joy was sparse but intense when it did appear. I wonder what exactly sparked these moments -- did people smile as they maintained their poise and kept their cool throughout a heated debate? Or perhaps panelists experienced joy and camaraderie if they found themselves agreeing with one of their peers.

Within the panels, overall gender diversity (38% female) was higher than I expected, though news networks still have not yet achieved an equal division of airtime between men and women. I see two possible explanations for this statistic. Either men and women are equally represented on panels and men tend to jump in the conversation first, or women are underrepresented and speech is proportional to representation. Regardless, these findings confirm what we already knew: women continue to face inequitable conditions in broadcast journalism.